Getting started with the Jetson Nano - part 3

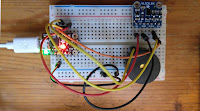

Jetson Nano image courtesy of NVIDIA/Pimoroni In part 2 of this series you prepared your Jetson Nano for software installation. In this part you'll install Jupyter Notebook, Jupyter lab, TensorFlow and some other software that is needed to run the first TensorFlow notebook. Once started, you can leave the software installation to run; it takes about an hour on a Nano in 10W power mode. It probably takes a little longer if you're using a 2.5A supply. There's a final manual stage which takes a couple of minutes. When that's complete you'll be able to work through the TensorFlow example, training a Neural Net to recognise item images from a Fashion database and then testing it in previously unseen images. Here's what you'll do, in a little more detail. Installing the software Open a terminal window on the Nano (A short-cut, crl-alt-T should do it). You'll be in your home directory; type git clone https://github.com/romilly/nano.g...