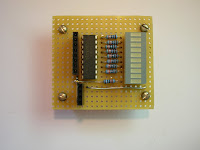

Veroduino Mk 2

I'm making good progress on my MicroWriter clone. I decided to start by building Mk 2 of my Veroduino . Mk 2 is more compact, and the green LED is connected to pin 13 by a jumper; one of my keyboard circuits needed to use pin 13 as an input, and the LED would have interfered with proper operation. Mk 2 uses as resonator rather than a crystal; it also corrects a defect in the Mk 1 design, which tied the analog reference voltage pin ( Aref ) to Vcc . Aref is not normally connected; if it is, it should linked to ground by a small capacitor, but that's only recommended if you are doing very precise analog measurements. I've corrected the schematic .